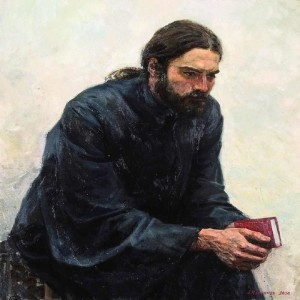

JOHN CASSIAN

How Cassian must be read

Cassian himself ceaselessly reiterated that you cannot understand the monastic life unless you are attempting to live it. The same could be said about the spiritual life. None of us are monks and few of us have embraced the spiritual life in the way that Cassian or the monks of his day did. We must then take care in the way we read his writings and approach them with humility - as beginners sitting at the feet of a master.

Background:

+ Lived c. 365-435 A.D.

+Time like our own:

season of councils - a period when the old and new, traditional and innovative surfaced in a myriad of combinations.

season of great experimentation that revealed the possibilities and limitations of monastic life.

season of doctrinal development when the Church was faced with questions concerning the relationship in the Trinity and the human and divine natures of Christ.

All of this is reflected in John's writings. In this they become an example of the problem faced by a Christian obliged to reconcile the past with the needs and burdens of his day. John was responding to the old problem of what to make of the life one has been given by God.

+ John's life:

John was not passive in his response. Somewhere about the year 380 he set out with a friend, Germanus, to visit the holy places of Palestine. In Bethlehem they became monks. But in those days the heart of the contemplative life was in Egypt and before long they went into that country, and visited in turn the famous holy men. For a time they lived as hermits under the guidance of Archebius, and then Cassian penetrated into the desert of Skete there to hunt out the anchorites concealed among its burning rocks and live with the monks in their cenobia.

For some reason unknown, about the year 400 he crossed over to Constantinople. He became a disciple of St. John Chrysostom, by whom he was ordained a deacon. When Chrysostom was uncanonically condemned and deposed, Cassian was among those sent to Rome to defend the Archbishop's cause to the Pope. He may have been ordained priest while in Rome.

Nothing more is known of his life until several years later, when he was in Marseilles.

It was at this time that Cassian was asked by a Bishop in the Diocese of Apt to write a

description of the practice of the monks in the east to be applied in a western monastery.

Cassian responded by choosing and interpreting the eastern traditions of the east to create

body of institutes suitable to the west.

Cassian had a long experience of the East. Meditating on the monastic life as presented to him in Egypt, he dismissed some suggestions and developed others. He certainly revered Egypt and its spirituality, but not everything he found there.

Out of the diversity of Egyptian ideas and practices, he began to create a coherent scheme of spirituality. For beginners in the monastic life and for those planning to found monasteries, John wrote the Institutes; and for those interested in the Egyptian ideal of the monk he composed twenty four

In these writings, it was Cassian's conviction that the monastic ideal can indeed be practiced.

The disciple needs common sense, moderation, perseverance, patience and a willingness to endure. If he has these, then the soul will find that the way of life to God is strengthening and joyful. Cassian's one warning, however, is that it does little good to share the insights of the Egyptian masters with those who are not prepared to receive them - - for those driven more by curiosity than by desire for God.

His intentions were simple.

First, he wanted to point to the highest modes of prayer.

Second, he wanted to show his monks how to create a good and harmonious community.

In this task, Cassian was a great ethical guide, a man of distinctive common sense and sensibility. The goal was perfection of life and the end of perfection was always charity. Perfection is full of movement - a direction toward, a loving aspiration after God © a loving response to the love of God.

In Cassian's view, the solitary way was best but the communal life of the coenobium was the necessary training ground of beginners; only when the ascetic had purged his soul of the common vices by the practice of virtue and mortification in community might he pass to the higher contemplation of the solitary. The coenobium is the kindergarten. After having lived with hermits in the desert, Cassian knowing his unworthiness and inability to embrace the higher practice returned to the kindergarten.

General Principles of the Institutes and Conferences

To search his writings for an intricate mystical ladder would be misguided. No system is

distinguishable in his writing, only certain general lines of thought.

The Monastery:

A. The Three Counsels: chastity, poverty and obedience

1. Cassian treats them not as vows but as virtues. Egyptian thought censured the practice of vows in the fear that they might lead either to pride or perjury.

chastity was not only abstention from corporal acts, but a limpid purity of soul,

cleansed from desire and virgin to all but God.

Poverty was not just the complete sacrifice of riches; abandonment of property was the

first step - the monk must pass to crush the sin and the desire that proceeds from

possessions and rise above the things that are not God. Beyond poverty is the separation

from all created things which is the condition of a pure love of God. All of this is a

conformity to the lowliness of the Lord - a descent to the want and poverty of Christ.

Obedience was paramount over every virtue, the ABCs in the learning of perfection.

The junior is not to trust his judgment, but to pronounce that to be good or bad which is

considered good or bad by his elder. They must reveal their thoughts of every kind, good

or bad, to receive comment and direction from their guide.

B. Admission of Novices

1. postulant must first lie outside the door for 10 days or longer. When he had shown

persistence, he entered the house to be stripped of his property and money and to

exchange the clothes of the world for the monastic dress. Secular garments were stored

as a silent reminder of expulsion in penalty for disobedience.

2. novice remained for a probationary year in the guest house excluded from full

membership of the community, instructed by an elder and responsible for visitors.

Cassian alone required so long a period before admission. At the end of the year the

novice was admitted formally and placed with other juniors under the supervision of a

senior monk.

C. Work:

1. seen not as creative nor even as primarily useful to the community, but as an

expedient method of keeping the body and mind occupied. Although work increases the

ability for contemplation, cures accidie, and acts as an aid to prayer, it need fulfill no

useful purpose. Manual labor preferred. However, writing and reading were customary exercises, but done with the purpose of growing in spiritual knowledge.

D. Worship:

1. motivated by humility

monks normally fled the idea ordination and the primitive practice was not to receive communion frequently for fear of partaking unworthily.

2. Cassian agreed with the view on ordination of which he saw himself unworthy

receiving and fear being drawn away from the quiet life. Communion, however, ought to

received often in order to receive medicine and cleansing for our souls. In his

monasteries they may have received daily!

3. Cassian introduced the eastern customs of common prayer, but adapted them for the

western monk. Egyptian custom celebrated Vespers and Nocturns only and allowed the

day time for continuous prayer in private.

a. Nocturns, the midnight office(matins): 12 psalms with prayers between each,

followed by two lesson from the OT and NT.

b. dawn office(lauds) - - immediately after matins: psalms 148-150.

c. morning office(prime): marked the beginning of the days work. psalms 51, 63,

90.

d. Terce, Sext, None: 3 psalms each, no lessons.

e. Vespers: 12 psalms and 2 lessons as at Nocturns

no compline, which first appeared in the rule of Benedict; psalmody was done in such a way to ensure understanding and prevent haste.

E. Acts of Mortification:

1. The search for God reveals the somber truth that the carnal instincts of human nature

are a barrier to pure worship and saintly character. A monk could only mould his will

upon the divine will if he conquered the instinctive self-centeredness of fallen humanity by ceaseless mortification; the sinful desires must die.

2. Cassian had three principles of mortification:

first it is an instrument to be used or unused according to need; secondly it is to Ã

remain secret; thirdly it must be restrained;

3. discretion was the indispensable virtue in the ascetic life; one must balance his way between the twin abysses of laxity and excessive austerity. Submission to the elders is nowhere more important than in the practice of mortification.

4. repudiating fanaticism, Cassian still demanded an exacting self-discipline in the

common and sober acts of austerity.

No comments yet. Be the first to say something!