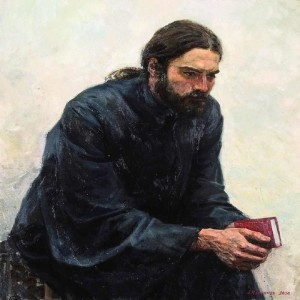

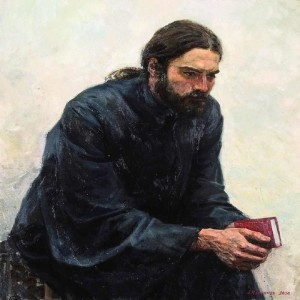

Philokalia Ministries

Episodes

Thursday Sep 03, 2015

Thursday Sep 03, 2015

Cassian and Germanus conclude there discussion with Abba Joseph by discussing the various kinds of feigned patience that mask the anger and bitterness that we can hold in our hearts towards others. Our words may be smoother than oil but become darts meant to wound. One can relish gaining the position of emotional advantage over the other while maintaining the perception of virtue; fasting or embracing greater silence in a diabolical fashion that only increases pride rather than fostering humility. Again, Abba Joseph reminds us that our desire should be not only to avoid anger ourselves but to sooth and calm the annoyance that arises in another's heart. We cannot be satisfied with our own sanctity; as if that could exist at the expense of others. We must enlarge our hearts so as to be able to receive the wrath of others and transform it through love and humility. By humble acts of reparation we should seek to diminish anger at every turn rather than inflame it.

Wednesday Aug 19, 2015

Conferences of St. John Cassian - Conference Sixteen on Friendship

Wednesday Aug 19, 2015

Wednesday Aug 19, 2015

You could feel the tension rise in the room as we began to make our way through Cassian's Conference on Friendship. It was startling, jarring and challenging while being absolutely beautiful and psychologically insightful at the same time. He gradually reveals to us what we value the most and what are hearts are truly set upon both for ourselves and others. He is, one might say, mercilessly realistic. I doubt any of us will view friendship or any other relationship in the same way! Some preliminary conversation about the relationship between Cassian and Germanus provides the occasion for Abba Joseph to raise the topic of the different kinds of friendship. After speaking of friendships founded on utility, kinship, and the like, he observes that they are subject to disintegration for one reason or other. Only a friendship based on a mutual desire for perfection is capable of surviving, and this desire must be strong in each friend; each must, in a word, share a common yearning for the good. When Germanus asks whether one friend should pursue what he perceives as good even against the wishes of the other friend, Joseph replies by saying that friends should never or rarely think differently about spiritual matters. Certainly they should never get into arguments with one another, which would indicate that in fact they were not of one mind in the first place. With this Joseph sets out six rules for maintaining friendship. It is interesting to see that these rules treat the subject more from the negative than from the positive side; that is, they aim more at preserving a friendship from collapse than at promoting it, although of course the former implies the latter. The final three rules, thus, touch upon controlling anger. Indeed, much of the rest of the conference has precisely this for its theme. The practice of humility and discretion-even to the point of seeking counsel from those who appear slow-witted, although actually they are more perceptive-is a major antidote to that divisiveness of will among friends from which anger springs. For the space of three chapters, the tenth to the twelfth, the discussion is so focused on discretion as to be particularly reminiscent of the second conference. Following these chapters Cassian distinguishes between love and affection: The former is a disposition that must be shown to all, whereas the latter is reserved to only a few. Affection itself exists in almost limitless variety: "For parents are loved in one way, spouses in another, brothers in another, and children in still another, and within the very web of these feelings there is a considerable distinction, since the love of parents for their children is not uniform" (16.14.2). The remaining half of the conference returns to the topic of dealing with anger, and in it Cassian demonstrates, as he did in previous conferences, his fine grasp of the workings of the human mind. He had already alluded in the ninth chapter to unacceptable conduct being concealed under the guise of "spiritual" behavior, and with the fifteenth chapter he takes this up again. There are brothers, for example, who cultivate the exasperating habit of singing psalms when someone is angry with them or they are angry with someone; they do this instead of seeking reconciliation and, undoubtedly, in order to manifest to any who might be looking on that they are superior to their own and others' emotions. Other brothers find it easier to treat pagans mildly and with restraint than to act in such wise toward their fellows; Cassian can only shake his head at this attitude. Still others give those who have irritated them the "silent treatment" or make provoking gestures that are more injurious than words; these persons deceive themselves by claiming that they have spoken nothing to disturb their confreres. (At this point Cassian distinguishes between deed and intention, which is a nuance that will assume a certain prominence in the next conference.) There are others, again, few though they may be, who stop eating when they are angry, although ordinarily they are able to endure fasting only with difficulty; persons of this sort must be qualified as sacrilegious for doing out of pride what they cannot do out of piety. Finally, there are some who knowingly set themselves up for a blow because of their all too artificially patient demeanor, to which they add insulting language; this patent abuse of the gospel injunction to turn the other cheek in fact indicates a wrathful spirit. Only the person who is strong, Cassian informs the reader, can sustain one who is weak without losing his temper. The weak, on the other hand, are easily moved to anger and to harsh words. To sum up, anger must never be surrendered to, and when discord has arisen reconciliation must be speedy. The concentration on anger in these pages that treat of friendship must at first appear startling, and Cassian may be criticized for not presenting a more optimistic vision of his subject. Where are the beautiful sentiments that lie scattered throughout much of Augustine's Confessions, say, or that can be found in Gregory Nazianzen, Paulinus of Nola, and others? Does friendship consist in nothing more than swallowing one's gorge? Yet Cassian is being painfully realistic: Anger is in fact one of the greatest threats, if not the greatest, to the very intimate relationship that he suggests in the opening pages of the conference. For a more idealized picture of friendship we must go to the first lines of the present conference or to those of the very first conference, in which Cassian describes his bond with Germanus. This is certainly the ideal, and we may only wish that its portrayal had been a little longer drawn out. A perhaps more important criticism is that most of what Cassian says is not really specific to friendship but can apply to almost any relationship. If the reader senses a slight unfocusing of the conference, it is probably for this reason.